Portrait of an Artist

Publication: Sunday Magazine | Date: September 2018

In 2004, photographer Jessie Casson was travelling the world and taking portrait shots of teenagers she randomly met. New Zealand was supposed to be a stopover – but she stayed. Almost 15 years (and three kids) later, she’s still here, the teenagers she shot are adults and she’s made a documentary about them. Emma Page reports.

On a Thursday evening earlier this month, photographer Jessie Casson held an informal launch party for her new documentary What Becomes of Me at the open-plan office space she shares with fellow creatives in Auckland’s Grey Lynn.

We meet there early on the morning of the party, the white-walled space productively humming. She makes us tea in the communal kitchen, giving the almond milk from the fridge a sniff before pouring it into the mugs. She is talking about buying bubbles for tonight's party, a celebration with friends and family that she is playfully calling “an almost red carpet event”, Her three children – Dylan, Otis and Iris aged 12, 8 and 6 respectively – are coming. They have all been intrigued by the project – Otis asked about it every night before bed.

“You kind of want to celebrate and share these things with your family,” she says, her subtle English accent rounding out the vowels. “Because they don’t happen very often.”

Casson is known for her distinct dynamic and honest portrait style. Her work, colourful and compelling, appears in publications around the globe and her portfolio is an album of some of our most well-known faces including Sir Ed, Karen Walker, Anika Moa and Buck Shelford. A portrait, she says, is all about relationships and she always wants to hear people’s stories.

“If the person doesn't feel comfortable and is not willing to give you themselves, then it's not going to be a good shot.”

This kind of rapport is the backbone of What Becomes of Me, a short and moving documentary, made in association with The Wireless and freely available to view online. For just over nine minutes, the camera follows Casson as she tracks down and reconnects with four New Zealanders she photographed nearly 15 years ago while holidaying in Aotearoa.

It was 2004, Casson was 27 years old and partway through a year-long, round-the-world honeymoon with her husband, Matt Hockey. The four documentary subjects – Alice, John, Matt, and Shane – were fresh-faced teenagers she had randomly met.

“Alice was a really sweet, quite naive girl with lots of ambition. She hoped to run and own dairy farms. I met her in Glenorchy at a bar and arranged to photograph her at dawn the next day. I would never have imagined that she’d get into heroin. In fact, she was already into heroin at this point, at 18. She was trying to get off, that’s why she was in Glenorchy. She’s had a huge amount thrown at her over the past 15 years. A drug addiction, breast cancer at 27. She has a 10-year-old son who lives with her half the time. I could have made the whole doco about her. She’s phenomenal.”

Casson had an established and burgeoning photography career in London and was using the backpacking trip as a vehicle for a personal series she named The Teenage Project. While travelling, through North, Central and South America from Mexico down to Argentina and then on to New Zealand, she would spot young people of interest, approach them and ask to take their picture.

It was, she says, like going hunting. “It felt like hunting... I would say to Matt, ‘We probably should go and shoot a teenager! We’d just walk around and see someone and I’d go, ‘I reckon they might be quite good.”

Her opening line? “I’ve got a slightly strange request.” Intrigued and perhaps disarmed by her open, honest manner, everyone she asked said yes – the four New Zealanders and 26 other young people dotted across the Americas. What followed was an intense interaction usually lasting no longer than an hour. Casson, who can speak and understand basic Spanish; would ask the teenager a set of nine questions, always the same ones, delving into their future hopes and dreams – “big life-changing questions which young people are much better at answering than adults.”

“Matt was skateboarding in Wanaka. When I met him 15 years later he had a photo of me and Matt (my husband) that he’d taken himself. He’s led quite a privileged life and he recognises that. He’s had emotional and financial support which may be some of the others haven’t. He’s a pilot who flies for Air New Zealand; he’s married. I think his journey has been less rebellious than I thought it would be.”

She recorded their answers on a dictaphone, later transcribing the answers by hand, answers she still has safely stored in her home office alongside the negatives of the portraits she shot on her hefty Hasselblad. medium-format camera.

It was before the digital revolution and the heavy camera needed a tripod and lighting gear. She got 12 shots per roll of film and only ever shot two rolls per person. Each shot counted. She would then befriend fellow British tourists, and if she trusted them, give them the film, the only copy of her work, to take back to the UK, where it went to a lab for developing.

“I didn’t see the pictures until eight months later”, she explains. “All of them at once. That’s like Christmas.”

“It must have been a Sunday. John was 19 and he was standing outside a church in Ponsonby. He wanted to be a minister – that was his dream. When I came back to try and find him again, all I had was the church. I sent the reverend there a photograph and he said, ‘Yes, he still comes to church with his family: John has three children now. He’s had a very serious accident where he fell off the back of a truck – he had a 50 percent chance of survival. He feels very lucky to still be alive.”

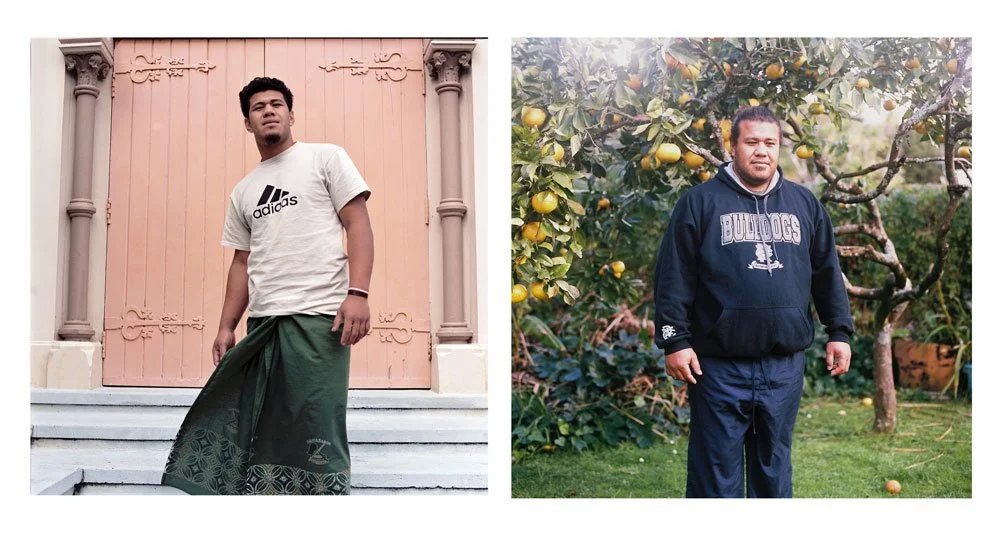

Now, nearly a decade and a half later, the resulting doco where she meets the four New Zealand subjects again and – literally dusting off the Hasselblad- retakes their portrait, is a moving reflection on how youthful aspirations survive the often perilous journey into adulthood. The still images are spectacular: two side-by-side photographs, encapsulating a then and now moment, taken on the same camera in the same style with only the march of time between them.

“I met Shane on Waipu Cove beach. We were stopping at a campground and he was fishing on the beach. (He still remembers that he didn't catch anything.) He was 18. He admitted that he was stoned when I first met him. And he also revealed that he was stoned during the second shoot, 15 years later, in Whangarei. He seems like someone still waiting to find his way.”

The documentary has been well received and next year Casson plans to repeat the process, only on a much grander scale. In September 2019, she will pack up the Hasselblad and along with Matt and the kids board a plane to Mexico where they will spend four months retracing their 15-year-old steps in search of the 26 teenagers, all now in their 30s.

So far she has tracked down five of them. “I always said, 'We’ll go back and find these people.”

Adventurous and always ready with a self-made project, Casson is not so intrepid that she can completely override the internal voices of doubt, the “what if this happens” on repeat, related to taking young children on such a trip.

“There is part of me that is terrified,” she admits. But she believes the memories and the experience will make it worthwhile. “And the other voice in my head goes, ‘It will be fine, it will be absolutely fine.”

Casson grew up in North East England “in the middle of nowhere”. Her mother was a yoga teacher, her father a consultant and an enthusiastic amateur photographer who had a darkroom. Casson got her first pinhole camera when she was nine. She loved it immediately.

There was no television in the house, play was outside and they ate a vegetarian diet. She felt different from everyone else.

“I do wonder if having to find a way to deal with difference is what gives me the strength to go out and just pursue my own ideas regardless. If I believe in it, then it's going to work.”

She laughs, letting the next sentence hang happily incomplete in the air: “Sometimes they don't work but…”

These days Auckland is home. She never did complete that round-the-world honeymoon. The plan stalled in New Zealand back in 2004 when the newlyweds fell for both the landscape – “the South Island is like Scotland on steroids” – and the friendly, open people who inhabit it. They bought a car for $500, drove around, liked what they saw, applied for residency and, helped along by the fact that Hockey, a commercial leasing agent, worked in an occupation that featured on the skill shortage list, got it and never left.

“We weren't ready to go home”, says Casson. “We wanted to carry on our adventure and the more I live here the more I think we’ve hit the jackpot.”